Interview with Gao JianThere was a time in the not-to-distant past when Tanglang was a rarity in Australia, outside of Zhao Zhuxi’s Taiji Tanglang Viet-Chinese descendants in the East coast and the Luo Guangyu lineage Qixing Tanglang taught in Perth. Mantis Boxing originating from the PRC was virtually unheard of until the 1990’s and it was indeed a blessing that a master of a particularly unique brand of Tanglang would eventually make his presence known in Victoria. Luckier still, he has decided to share the Liuhe Tanglang of his master Ma Hanqing with the world. It is with great pleasure that I introduce Mr Gao Jian.

|

BT: Thanks for taking the time to share a few stories about your martial life. Could you please start by telling the readers a little about your background?

GJ: First of all, thank you very much for conducting such a valuable interview! I was surprised by the thoroughness and deepness of the research you’ve made for the interview.

Cheers. I can’t hide my interest in the subject matter.

OK, let’s start: I was born in Wuhan city(武汉市) of Hubei province(湖北省), China. I’m the oldest son in Gao family which has four boys and a girl. My ancestral home was in a remote rural village in Sichuan province (四川).

How did you come to migrate to Australia?

I came to Australia in July 1988 as an overseas student. In1989, Australian government decided to grant a four year special visa to those Chinese students who were already in Australia when China had a turbulent situation at that time. As the result of the special visa granting, I was given a permanent residency thereafter.

I believe your father was also a martial artist (and was possibly your first teacher)? What kind of boxing did he teach you? Are there any other martial artists in the Gao family?

My father was my first Taiji enlightener, but he was not a martial artist. He taught Taiji in a small local community mainly as a recreational activity for health. He learnt Yang Style Taji in 1950s from Master Cui Yishi (崔毅士) who was one of the disciples of renowned grant master Yang Chengfu (杨澄甫), but my father never deepened his study in the area and never became a formal student of master Cui. My father passed away in 2005 at the age of 91.

How did you come to train under Beijing legend - the late, great Ma Hanqing?

Thank you for raising this question; it makes me recall this vivid memory. In 1973, I was in trouble to improve my Taiji level and was struggling to get rid of my awkward habit in Yang Style Taiji movements. One morning, I met my friend Zhong Guoyuan (钟国元) who at that time was practising Meihua Tanglang (Plum Blossom Praying Mantis Boxing); during chatting, I expressed my worries in regarding to my Taiji problems. Zhong is a friend with whom I started friendship back in those years when I was a 16 year old teenager and this friendship is still with us up to now. Unfortunately Zhong never became a formal student of Ma Hanqing(马汉青. “My teacher Ma teaches Taiji too, he is a very good Wushu and Taiji master ---” Zhong replied, “Oh? Could my problem be corrected by your teacher?” I asked; Zhong hesitated a little while, and then agreed to try it for me, but there was no guarantee given. A few days later, he came to my place and told me that he was allowed to bring me to meet his teacher---

The late autumn evening in Beijing was a little cold, Zhong and I took a bus to go to Mr.Ma Hanqing’s home after we finished our work on the day. It was a typical old Beijing style courtyard (四合院) in ‘Dong Zhi Men Nei Da Jie’ (东直门内大街) of Eastern district of Beijing city, Mr. Ma’s home was one of a few families living in the yard. Zhong lightly knocked on the door of Ma’s hose, with a sonorous voice: “Come in please”, the door was opened and Mr.Ma Hanqing was in front of us: he was in his early 50’s age, average sized but solid built, gentle manner with a vigilant blaze in his eyes. We greeted Ma Laoshi (马老师) first, then got in, set down and started talking. Zhong briefly introduced me and my situation, and then I expressed my worries and wishes. Mr. Ma asked me to show some of the movements for him, I did so. When I finished my show, I saw Mr. Ma was smiling: “yours is not Taiji.” He said, “because your footing stances were those stuff shown in Peking opera, they are stances for Peking opera or dancing, but they are useless in martial arts; that was probably the reason why you felt awkward.” With a big shock, I pleaded Mr. Ma to correct my footing stances. “I cannot correct you as I don’t practise Yang Style Taiji, mine is Wu Style (吴氏), and it is different” he replied.

After I had expressed my strong will to learn decent Taiji, Mr. Ma nodded, and then said to me: “I can only teach Wu Style Taiji. My teacher is Yang Yuting Laoshi(杨禹廷老师), this one (the lineage) is a decent one. But you’ll have to start from beginning as an absolute beginner and stop practising your dancing.” We all laughed --- This was the day that influenced my life forever.

What did a typical training session under your master consist of?

My training session was pretty much like ‘one on one’ tuition although sometimes joined by my brother in later years (my brother never became a formal student). Except about once in every three months in a park (Temple of Earth – 地坛), in most times, I learned and trained in the home of my Master. Usually I took a suburb bus to go to my teacher’s home after I finished my work every Monday evening and got back to my home by last bus in the night. The sessions consisted of Mr. Ma’s instructions, advice, demonstrations and my practice. For the refining and corrections in the park in later years, it also contained our pushing hand drills or ‘chai shou’ (拆手). Under his instructions, those basic conditioning exercises (基本功) like Stretching, Ya Tui & Ti Tui and so on were my own task to get them done in my own spare time.

GJ: First of all, thank you very much for conducting such a valuable interview! I was surprised by the thoroughness and deepness of the research you’ve made for the interview.

Cheers. I can’t hide my interest in the subject matter.

OK, let’s start: I was born in Wuhan city(武汉市) of Hubei province(湖北省), China. I’m the oldest son in Gao family which has four boys and a girl. My ancestral home was in a remote rural village in Sichuan province (四川).

How did you come to migrate to Australia?

I came to Australia in July 1988 as an overseas student. In1989, Australian government decided to grant a four year special visa to those Chinese students who were already in Australia when China had a turbulent situation at that time. As the result of the special visa granting, I was given a permanent residency thereafter.

I believe your father was also a martial artist (and was possibly your first teacher)? What kind of boxing did he teach you? Are there any other martial artists in the Gao family?

My father was my first Taiji enlightener, but he was not a martial artist. He taught Taiji in a small local community mainly as a recreational activity for health. He learnt Yang Style Taji in 1950s from Master Cui Yishi (崔毅士) who was one of the disciples of renowned grant master Yang Chengfu (杨澄甫), but my father never deepened his study in the area and never became a formal student of master Cui. My father passed away in 2005 at the age of 91.

How did you come to train under Beijing legend - the late, great Ma Hanqing?

Thank you for raising this question; it makes me recall this vivid memory. In 1973, I was in trouble to improve my Taiji level and was struggling to get rid of my awkward habit in Yang Style Taiji movements. One morning, I met my friend Zhong Guoyuan (钟国元) who at that time was practising Meihua Tanglang (Plum Blossom Praying Mantis Boxing); during chatting, I expressed my worries in regarding to my Taiji problems. Zhong is a friend with whom I started friendship back in those years when I was a 16 year old teenager and this friendship is still with us up to now. Unfortunately Zhong never became a formal student of Ma Hanqing(马汉青. “My teacher Ma teaches Taiji too, he is a very good Wushu and Taiji master ---” Zhong replied, “Oh? Could my problem be corrected by your teacher?” I asked; Zhong hesitated a little while, and then agreed to try it for me, but there was no guarantee given. A few days later, he came to my place and told me that he was allowed to bring me to meet his teacher---

The late autumn evening in Beijing was a little cold, Zhong and I took a bus to go to Mr.Ma Hanqing’s home after we finished our work on the day. It was a typical old Beijing style courtyard (四合院) in ‘Dong Zhi Men Nei Da Jie’ (东直门内大街) of Eastern district of Beijing city, Mr. Ma’s home was one of a few families living in the yard. Zhong lightly knocked on the door of Ma’s hose, with a sonorous voice: “Come in please”, the door was opened and Mr.Ma Hanqing was in front of us: he was in his early 50’s age, average sized but solid built, gentle manner with a vigilant blaze in his eyes. We greeted Ma Laoshi (马老师) first, then got in, set down and started talking. Zhong briefly introduced me and my situation, and then I expressed my worries and wishes. Mr. Ma asked me to show some of the movements for him, I did so. When I finished my show, I saw Mr. Ma was smiling: “yours is not Taiji.” He said, “because your footing stances were those stuff shown in Peking opera, they are stances for Peking opera or dancing, but they are useless in martial arts; that was probably the reason why you felt awkward.” With a big shock, I pleaded Mr. Ma to correct my footing stances. “I cannot correct you as I don’t practise Yang Style Taiji, mine is Wu Style (吴氏), and it is different” he replied.

After I had expressed my strong will to learn decent Taiji, Mr. Ma nodded, and then said to me: “I can only teach Wu Style Taiji. My teacher is Yang Yuting Laoshi(杨禹廷老师), this one (the lineage) is a decent one. But you’ll have to start from beginning as an absolute beginner and stop practising your dancing.” We all laughed --- This was the day that influenced my life forever.

What did a typical training session under your master consist of?

My training session was pretty much like ‘one on one’ tuition although sometimes joined by my brother in later years (my brother never became a formal student). Except about once in every three months in a park (Temple of Earth – 地坛), in most times, I learned and trained in the home of my Master. Usually I took a suburb bus to go to my teacher’s home after I finished my work every Monday evening and got back to my home by last bus in the night. The sessions consisted of Mr. Ma’s instructions, advice, demonstrations and my practice. For the refining and corrections in the park in later years, it also contained our pushing hand drills or ‘chai shou’ (拆手). Under his instructions, those basic conditioning exercises (基本功) like Stretching, Ya Tui & Ti Tui and so on were my own task to get them done in my own spare time.

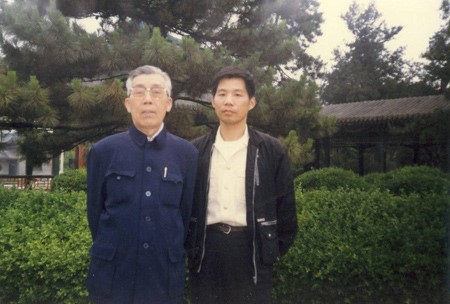

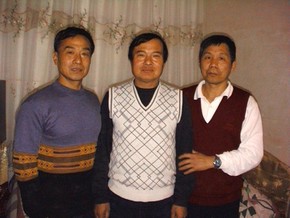

With Master Ma Hanqing, Beijing 1988

With Master Ma Hanqing, Beijing 1988

Master Ma is widely known in the west, perhaps due largely to exposure on the internet. Was it a big step for you to adopt modern methods of propagation such as the internet, considering your own experiences learning martial arts in a traditional and relatively closed environment?

Yes, it took me quite a few years to consider formally teaching the Chinese martial arts. To be honest, without my wife’s support and encouragement, I would not be able to start and to continue my teaching. I should also admit that without my son’s help, I would not be able to get my website published too.

It seems that you specialised in Liuhe Tanglang as opposed to your teacher’s Taijimeihua. How was that decision made and did it have to do with your strong Taiji background?

I would rather say that mine is part of my teacher’s, instead of opposed to my teacher’s. Actually, at the time when I was learning Liuhe Tanglang, Taijimeihua Tanglang was still called ‘Meihua Tanglang’ in my lineage.

That’s a very interesting point. It was the same for some other Haojia (Hao Family) descended schools in Shandong.

Master Ma has told me that Meihua is better for showing and Liuhe is better for fighting (梅花好看,六合好用.). He especially indicated the advantage of ‘Duan Chui (Short punches)’ in fighting.

As the question of ‘how was the decision made’, yes it does have something to do with my Taiji background. At the time when Master Ma started teaching Liuhe Tanglang, I had practised Wu Style Taiji over three years and started learning pushing hand with him. One day, when I finished my training with him, Master Ma said: “Your Taiji is doing very well, but be aware that Taiji is a very slow unfolding martial art, normally ten years practice of Taiji is still not good enough. I think you can learn Liuhe Tanglang now to supplement your Taiji skill and this one is very practical---” From nearly 40 years of practising both arts under his teaching, I found that Liuhe Tanglang does have a strong correlation with Taiji because they all have ’Zhan, Nian, Lian Sui’ (粘,黏,连,随) nature and both can supplement each other.

Did you get the chance to study any of the many other systems that Ma Shifu had mastered, such as Cha Quan, Xingyi etc?

I only got the chance to study Wu Style Taiji and Liuhe Tanglang from my master and I feel fortunate enough to still mastering these two arts up to now. In other words: I’m still a student in researching these two wonderful arts, no chance to study others.

Do you find that people require a solid background in some other style before attempting to study Liuhe Tanglang? In certain families, Liuhe seems to have been introduced only to those at an advanced level.

My opinion on this question is this: It is a reasonable requirement, but it is not necessarily “Has to be so”, because it will depend on different individuals. The postures and movements in Liuhe Tanglang routines are not too difficult to do, but the power converting and launching with its weave like momentum are quite difficult to manoeuvre as it has ‘Zhan, Nian, Lian, Sui (粘,黏,连,随)’ and anti(反)‘Zhan, Nian, Lian, Sui’ characteristics in its nature. The Chinese words used in table tennis are the best way to express the nature of the Liuhe Tanglang – 快攻加弧圈; it means a particular style of the ball playing: the speed of the ball plus the spin of the ball and this kind of style is quite difficult to master both in table tennis and in martial arts.

An interesting analogy! There is certainly more than meets the eye to Liuhe Tanglang movement.

From this point of view, it would be better for a practitioner to gain some senses in regarding to ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ martial arts natures before engaging Liuhe Tanglang. For example, I personally learned Liuhe Tanglang three years after my Wu Style Taiji practice under my master Ma Hanqing.

I believe that even into his later years Ma Hanqing was very conservative in his approach to passing on Liuhe Tanglang. Am I wrong in saying that he initially advised you to keep it for yourself?

You are not wrong in saying so. In fact, Master Ma did advise me to keep Liuhe Tanglang for my personal use instead of teaching it before I left China for Australia in 1988. He also passed on the Wu Style Taiji (Northern) lineage and Liuhe Tanglang lineage charts (relevant senior generation figures) to me in case I need them. One thing I need to make it clear in here by the way: when passing on the Liuhe Tanglang lineage chart, he clearly indicated that up to the year 1988, from his best knowledge, there were only two persons in Beijing who decently learned Liuhe Tanglang Quan from Grant master Shan Xiangling (单香陵): one was Ma Hanqing, the other one was his Kung fu brother Li Bingci(李秉慈).

Yes, it took me quite a few years to consider formally teaching the Chinese martial arts. To be honest, without my wife’s support and encouragement, I would not be able to start and to continue my teaching. I should also admit that without my son’s help, I would not be able to get my website published too.

It seems that you specialised in Liuhe Tanglang as opposed to your teacher’s Taijimeihua. How was that decision made and did it have to do with your strong Taiji background?

I would rather say that mine is part of my teacher’s, instead of opposed to my teacher’s. Actually, at the time when I was learning Liuhe Tanglang, Taijimeihua Tanglang was still called ‘Meihua Tanglang’ in my lineage.

That’s a very interesting point. It was the same for some other Haojia (Hao Family) descended schools in Shandong.

Master Ma has told me that Meihua is better for showing and Liuhe is better for fighting (梅花好看,六合好用.). He especially indicated the advantage of ‘Duan Chui (Short punches)’ in fighting.

As the question of ‘how was the decision made’, yes it does have something to do with my Taiji background. At the time when Master Ma started teaching Liuhe Tanglang, I had practised Wu Style Taiji over three years and started learning pushing hand with him. One day, when I finished my training with him, Master Ma said: “Your Taiji is doing very well, but be aware that Taiji is a very slow unfolding martial art, normally ten years practice of Taiji is still not good enough. I think you can learn Liuhe Tanglang now to supplement your Taiji skill and this one is very practical---” From nearly 40 years of practising both arts under his teaching, I found that Liuhe Tanglang does have a strong correlation with Taiji because they all have ’Zhan, Nian, Lian Sui’ (粘,黏,连,随) nature and both can supplement each other.

Did you get the chance to study any of the many other systems that Ma Shifu had mastered, such as Cha Quan, Xingyi etc?

I only got the chance to study Wu Style Taiji and Liuhe Tanglang from my master and I feel fortunate enough to still mastering these two arts up to now. In other words: I’m still a student in researching these two wonderful arts, no chance to study others.

Do you find that people require a solid background in some other style before attempting to study Liuhe Tanglang? In certain families, Liuhe seems to have been introduced only to those at an advanced level.

My opinion on this question is this: It is a reasonable requirement, but it is not necessarily “Has to be so”, because it will depend on different individuals. The postures and movements in Liuhe Tanglang routines are not too difficult to do, but the power converting and launching with its weave like momentum are quite difficult to manoeuvre as it has ‘Zhan, Nian, Lian, Sui (粘,黏,连,随)’ and anti(反)‘Zhan, Nian, Lian, Sui’ characteristics in its nature. The Chinese words used in table tennis are the best way to express the nature of the Liuhe Tanglang – 快攻加弧圈; it means a particular style of the ball playing: the speed of the ball plus the spin of the ball and this kind of style is quite difficult to master both in table tennis and in martial arts.

An interesting analogy! There is certainly more than meets the eye to Liuhe Tanglang movement.

From this point of view, it would be better for a practitioner to gain some senses in regarding to ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ martial arts natures before engaging Liuhe Tanglang. For example, I personally learned Liuhe Tanglang three years after my Wu Style Taiji practice under my master Ma Hanqing.

I believe that even into his later years Ma Hanqing was very conservative in his approach to passing on Liuhe Tanglang. Am I wrong in saying that he initially advised you to keep it for yourself?

You are not wrong in saying so. In fact, Master Ma did advise me to keep Liuhe Tanglang for my personal use instead of teaching it before I left China for Australia in 1988. He also passed on the Wu Style Taiji (Northern) lineage and Liuhe Tanglang lineage charts (relevant senior generation figures) to me in case I need them. One thing I need to make it clear in here by the way: when passing on the Liuhe Tanglang lineage chart, he clearly indicated that up to the year 1988, from his best knowledge, there were only two persons in Beijing who decently learned Liuhe Tanglang Quan from Grant master Shan Xiangling (单香陵): one was Ma Hanqing, the other one was his Kung fu brother Li Bingci(李秉慈).

Gao Jian and brother Gao Peng

Gao Jian and brother Gao Peng

Liuhe Tanglang is becoming increasingly popular with overseas practitioners these days, with many now making pilgrimages to Beijing, Yantai and surrounding districts to train. The internet and availability of instructional books and video has made it accessible to an even wider audience. It does not seem so long ago that Liuhe Tanglang enjoyed something of a low profile and perhaps an element of exclusivity.

I agree with you. Two reasons kept Liuhe Tanglang with a low profile in the past:

Substantially quite dangerous: High applicable character in bare hand fighting and its deadly momentum.

Visually not too attractive: Relatively difficult power manoeuvre and less impressive external manner.

In my opinion, it is such two reasons that make Liuhe Tanglang so popular now amongst experienced martial artists in the world.

The comprehensive DVD you released a few years back (Six Harmonies Praying Mantis Boxing) was very much appreciated by the Tanglang community. You have now also produced one on Double-Handed Mantis Sword and a couple focusing on Wu Style Taiji. Was it a difficult choice for you to record and release what amounts to 40+ years of your own hard work to the general public? Was preservation of these materials a major goal?

My decision on making and releasing these DVDs was mainly based on my liability owed to my master’s teaching. The ‘Six Harmonies Praying Mantis Boxing’ DVD was my first attempt. Being unexperienced in filming and DVD making at that time, it was not an ideal product from my point of view. Apart from my sense of liability, one incident was also part of the reason why the first DVD was made: In 2003, I was told that a renowned visiting master from Beijing who had written a book in regarding to Liuhe Tanglang was going to demonstrate Liuhe Tanglang in that year’s Wushu/Taiji competition in Melbourne and he was going to conduct some workshops including Liuhe Tanglang in Australia as well.

I was a little surprised as I remembered that my master never mentioned this man’s Tanglang history to me before. After I was shocked to see the different manner of Liuhe Tanglang he demonstrated in the show, I decided to invite the master to my home so that I could sort out of the puzzle. The master had a lunch with me in my home; we talked about Beijing’s martial arts figures and Liuhe Tanglang history. During the lunch, he gave me his newly published book (Liuhe Tanglang Quan) as a gift. It was going well until he mentioned my master’s political history which in my view was a deliberate smear as my master was mistreated under the same mentioned name during China’s ‘cultural revolution’. For diplomatic reason, I did not argue with the master. Although his personality lost its decency by doing so, he is a senior anyway ---

Such a shame. I have heard of this kind of thing over and over. The Cultural Revolution lives on, even after so many years...

To verify the history of the development of Liuhe Tanglang in Beijing, I went back to China in 2004 to consult with some of my Kung Fu brothers, especially with Ma Lei (马雷) and then worked out the reason why my master Ma Hanqing never mentioned such history to me before. Of course, I would rather remain this history not to be publically shared from my site---

That’s understandable.

After coming back from Beijing in 2004, I decided to teach Liuhe Tanglang publicly and to make the Liuhe Tanglang DVD so that more people would make their own judgement on what is the right way of practising Liuhe Tanglang. I believe that this is the best way to respond to my master’s advice to me in 1988. From this point of view, I would say that preservation of right materials is indeed a major goal.

I agree with you. Two reasons kept Liuhe Tanglang with a low profile in the past:

Substantially quite dangerous: High applicable character in bare hand fighting and its deadly momentum.

Visually not too attractive: Relatively difficult power manoeuvre and less impressive external manner.

In my opinion, it is such two reasons that make Liuhe Tanglang so popular now amongst experienced martial artists in the world.

The comprehensive DVD you released a few years back (Six Harmonies Praying Mantis Boxing) was very much appreciated by the Tanglang community. You have now also produced one on Double-Handed Mantis Sword and a couple focusing on Wu Style Taiji. Was it a difficult choice for you to record and release what amounts to 40+ years of your own hard work to the general public? Was preservation of these materials a major goal?

My decision on making and releasing these DVDs was mainly based on my liability owed to my master’s teaching. The ‘Six Harmonies Praying Mantis Boxing’ DVD was my first attempt. Being unexperienced in filming and DVD making at that time, it was not an ideal product from my point of view. Apart from my sense of liability, one incident was also part of the reason why the first DVD was made: In 2003, I was told that a renowned visiting master from Beijing who had written a book in regarding to Liuhe Tanglang was going to demonstrate Liuhe Tanglang in that year’s Wushu/Taiji competition in Melbourne and he was going to conduct some workshops including Liuhe Tanglang in Australia as well.

I was a little surprised as I remembered that my master never mentioned this man’s Tanglang history to me before. After I was shocked to see the different manner of Liuhe Tanglang he demonstrated in the show, I decided to invite the master to my home so that I could sort out of the puzzle. The master had a lunch with me in my home; we talked about Beijing’s martial arts figures and Liuhe Tanglang history. During the lunch, he gave me his newly published book (Liuhe Tanglang Quan) as a gift. It was going well until he mentioned my master’s political history which in my view was a deliberate smear as my master was mistreated under the same mentioned name during China’s ‘cultural revolution’. For diplomatic reason, I did not argue with the master. Although his personality lost its decency by doing so, he is a senior anyway ---

Such a shame. I have heard of this kind of thing over and over. The Cultural Revolution lives on, even after so many years...

To verify the history of the development of Liuhe Tanglang in Beijing, I went back to China in 2004 to consult with some of my Kung Fu brothers, especially with Ma Lei (马雷) and then worked out the reason why my master Ma Hanqing never mentioned such history to me before. Of course, I would rather remain this history not to be publically shared from my site---

That’s understandable.

After coming back from Beijing in 2004, I decided to teach Liuhe Tanglang publicly and to make the Liuhe Tanglang DVD so that more people would make their own judgement on what is the right way of practising Liuhe Tanglang. I believe that this is the best way to respond to my master’s advice to me in 1988. From this point of view, I would say that preservation of right materials is indeed a major goal.

Shuang Shou Tanglang Jian

Shuang Shou Tanglang Jian

Do you think video footage is a valuable training tool? If so, at what phase of the training should it be introduced?

Yes it is. For beginners it works as a guideline of the style, for experienced martial artists, it can give an insight of what is happening in the style. So it can be used in any phase.

Are you an advocate of modern, non-martial training methods to enhance physical condition? If so, do you encourage your students to undertake such training outside of your classes or do you also cover this in your regular classes?

I’m not in such a role although I do believe that modern Wushu training can improve a practitioner’s body condition effectively. But the excessive exercise for jumping higher, doing more difficult movements or having more choreographic visual excitement to get a higher score in a competition have made too much injuries for athletes. Above all, the important point is: these choreographic movements have nothing to do with martial applications.

How about weight training? I know Liuhe Tanglang has its own iron ball and jar gripping strength training methods, but do you advocate any ‘modern’ types of strength training?

We don’t have these training methods although I do advise students to do gripping practice. In my opinion, cooperative muscle function is more important than individual muscle function. Personally I like the muscles of swimmers, not the muscles of body builders.

Did you have the opportunity to practice iron palm in your youth? If so, can you briefly outline the iron palm method of Liuhe Tanglang?

I did have opportunity to do such things, but I did not practise iron palm; instead, I did some bean rubbing in those years which was easier and handier to carry out.

What about pai da gong or various forms of qigong that condition the body to withstand hard strikes? Do you continue to teach such things today or are they perhaps not so relevant?

I personally have been trained these Pai Da gong under my master in the past and some time I still practise them now. I mainly practise them by myself, normally I pat my hands and forearms on a tree trunk or hit one forearm with the other palm; then pat my body with both palms and fists lightly. I teach them in my class too.

What forms of qigong, if any, did Ma Shifu teach?

He did not teach Qigong in those years, I learned Daoist Qigong from a Chinese doctor in China.

Tanglang has many partner drills and duilian exercises. Did you learn any versions? Liuhe Tanglang (in Shandong) has some excellent paired stick and spear drills, for example.

I only had opportunity to practise some bare hand drills with my master and my brother. Such as Mo Pan Shou (磨盘手) v Shi Zhi chui(十字捶),Tie Ci Lian Huan(铁刺连环) v San Chui (三捶),Ba Wang Zhai Kui (霸王摘盔) and so on. I was not aware any weapon drills in Liuhe Tanglang during those years. At the time when I was learning in 1970s and 1980s, Liuhe Tanglang only had seven bare hand routine taolu (sets) as far as I can recall now.

Do you spend much of your time practising or teaching weapons these days? What is your view on the role of weapons training in the modern era?

Not really at the moment. My view on weapons training in the modern times is this: they are mainly the supplements to improve bare hand ability, as we are not in cold weapon fighting age today. My favourite weapon is my bare hands as I’m not very good in using apparatus.

Yes it is. For beginners it works as a guideline of the style, for experienced martial artists, it can give an insight of what is happening in the style. So it can be used in any phase.

Are you an advocate of modern, non-martial training methods to enhance physical condition? If so, do you encourage your students to undertake such training outside of your classes or do you also cover this in your regular classes?

I’m not in such a role although I do believe that modern Wushu training can improve a practitioner’s body condition effectively. But the excessive exercise for jumping higher, doing more difficult movements or having more choreographic visual excitement to get a higher score in a competition have made too much injuries for athletes. Above all, the important point is: these choreographic movements have nothing to do with martial applications.

How about weight training? I know Liuhe Tanglang has its own iron ball and jar gripping strength training methods, but do you advocate any ‘modern’ types of strength training?

We don’t have these training methods although I do advise students to do gripping practice. In my opinion, cooperative muscle function is more important than individual muscle function. Personally I like the muscles of swimmers, not the muscles of body builders.

Did you have the opportunity to practice iron palm in your youth? If so, can you briefly outline the iron palm method of Liuhe Tanglang?

I did have opportunity to do such things, but I did not practise iron palm; instead, I did some bean rubbing in those years which was easier and handier to carry out.

What about pai da gong or various forms of qigong that condition the body to withstand hard strikes? Do you continue to teach such things today or are they perhaps not so relevant?

I personally have been trained these Pai Da gong under my master in the past and some time I still practise them now. I mainly practise them by myself, normally I pat my hands and forearms on a tree trunk or hit one forearm with the other palm; then pat my body with both palms and fists lightly. I teach them in my class too.

What forms of qigong, if any, did Ma Shifu teach?

He did not teach Qigong in those years, I learned Daoist Qigong from a Chinese doctor in China.

Tanglang has many partner drills and duilian exercises. Did you learn any versions? Liuhe Tanglang (in Shandong) has some excellent paired stick and spear drills, for example.

I only had opportunity to practise some bare hand drills with my master and my brother. Such as Mo Pan Shou (磨盘手) v Shi Zhi chui(十字捶),Tie Ci Lian Huan(铁刺连环) v San Chui (三捶),Ba Wang Zhai Kui (霸王摘盔) and so on. I was not aware any weapon drills in Liuhe Tanglang during those years. At the time when I was learning in 1970s and 1980s, Liuhe Tanglang only had seven bare hand routine taolu (sets) as far as I can recall now.

Do you spend much of your time practising or teaching weapons these days? What is your view on the role of weapons training in the modern era?

Not really at the moment. My view on weapons training in the modern times is this: they are mainly the supplements to improve bare hand ability, as we are not in cold weapon fighting age today. My favourite weapon is my bare hands as I’m not very good in using apparatus.

Gao with Wang Xishun and disciples, Beijing 2004

Gao with Wang Xishun and disciples, Beijing 2004

You founded the Harmonious Art Research, Australia (HARA) in 2004. It is a unique organisation as far as the promotion of Chinese martial culture goes and it is clear that you do not go in for the strict hierarchical structure of some institutions and encourage a sense of equality. Have you found this kind of set up is conducive to achieving excellence in the systems that you teach? For example, I would not guess that you studied in a similar atmosphere. What are some of the challenges of teaching in the relative luxury of a country with one of the world’s highest living standards and how big of a factor is the cultural difference?

You’ve reached an important area and I appreciate your insight.

Chinese martial arts, if being searched to its extreme end, would be a matter of culture. Chinese Kung Fu actually is not just about fighting arts, it is a school of literature, a heritage, and a spirit. Chinese culture, although has some elements of Legalism (法家) and Mohism (墨家), basically is composite of three philosophies: The Daoist (道家), The Confucianist(儒家)and Buddhist(佛家). Among them, Confucianist (and its religion Confucianism) was the one promoted by most Chinese rulers throughout history. Although derived from the Daoist doctrine, it was developed quite contrary to its origins over thousands of years. It was a major advocate of patriarchy, a promoter of feudal ethical code (封建礼教) and a solvent for the mixture of gentleman and hypocrite.

From my point of view, since the Song Dynasty (宋朝), Chinese society has been dominated by Confucian extremists (not the original Confucianist), the doctrine of feudal ethical code has influenced Chinese social ideology for a long time, even up to now. Acknowledge it or not, as a typical Chinese, we don’t have much sense of what western society (such as Australia) has: the liberty, the equality and the democracy. Chinese martial arts society therefore, as a part of Chinese ‘special’ society, has lots of feudal ethical elements in it. In some cases, it has more strict ethical codes. Almost all the schools in Chinese martial arts have strict etiquette, the hierarchy concept is the very important ‘basic knowledge’ if you become an ‘insider of the martial arts circle (武林中人)’. Normally, there is not much space for liberty, equality and democracy in this area – the masters are the rulers of their schools, the students, especially the disciples would be the ‘pulp’, they do what the master said; if you don’t do it – “get out!” and you are finished.

No doubt, this kind of patriarchal hierarchy is very difficult to be accepted in western world such as Australia. I think this would be a big challenge for promoting traditional Chinese Kung Fu in western countries for both sides (teacher and student).

I agree that for many it is a very foreign concept and in some respects, does not sit well with local values. However, there are also many westerners who crave this aspect of traditional Chinese culture and who are actually attracted to the practice of Kung Fu primarily because of such things.

Maybe you and I look at the matter from a different angle. I acknowledge the attraction of Chinese culture to many westerners, but I’m also aware that ‘to crave’ something doesn’t always give us the right stuff. When China opened its door to the world and to Chinese people in 1980s, lots of Chinese craved the ‘American culture’ at that time; 30 years later, many of these Chinese have found out that such ‘culture’ is not what they needed, at least not 100% needed. Of course, alien culture amazes local people and hence attracts them, but we should distinguish and then pursue the essence of the culture, not the rubbish in it. Daoist, Confucianist and Buddhist are all important philosophies to Chinese culture, but they all have some rubbish in them, especially when people changed the ‘IST’ of philosophies into the ‘ISM’ of religions.

Actually I agree with you that this kind of cultural infatuation is generally not a positive thing. Often people are attracted for the wrong reasons in the first place; unfortunately this can result in a complete and dramatic rejection of all related cultural aspects later when the individual comes to some form of realisation. In some cases this seems to manifest in a borderline racist attitude. For example, there are many Westerners who would prefer to strip Kung Fu of all cultural elements and there seems to be an underlying sense of guilt amongst some for their involvement in a foreign pursuit in the first place.

Here we are! I hope our discussions in this area could be seen by some Chinese martial artists too, especially by some of highly skilled decent Chinese Wushu officials, should this interview been translated into Chinese language. Because, as an extension of our discussion on these two particular questions, what you and I observed and unveiled in here is the true reason why there are so many chaos in Chinese martial arts societies either in China and in the world. Again, this is actually a big subject as culture is a social ideology and it is an expressing way of psychology.

As a traditional Chinese and a traditional Kung Fu practitioner who later on has had the opportunity to compare the ideologies based on cultural differences, particularly after I settled in Australia, I have seen the advantage and disadvantage of these ethical codes in Chinese martial arts society. Surely, we need authority in our martial arts teachings; but it is not necessary to be patriarchal. I’m personally in favour of Daoist, it principally has the elements of liberty, equality and democracy; the most important thing is: it is natural, not artificial. I try to create an environment in which everyone feels they are being treated equally so that their sense of liberty can be released. This way, we can get rid of that rigid relationship in hierarchy; but at the same time, a true sense of Kung Fu skill levels or Kung Fu’s hierarchy can be formed in students mind. To me, this is most important as these students are self inspired naturally. In other words: they are awakening themselves, naturally!

My view on teacher’s title is this: no matter what title you’ve got, it is just a label. Although it is nice to have an attractive label, the important thing is the content. You can be called a master or Shifu or even a grand master and so on, but students are more concerned about the skill level you’ve got.

It’s definitely a consideration. But a good personality is just as, if not more important.

Yes, I agree. Plus, different individuals have different definitions on the name of “master”. Authority in teaching should be formed naturally. As an experienced martial arts practitioner, the lower the profile you keep the more respect you get. Also, your name is your best trade mark, it is for calling anyway! Why shall we put too much artificial titles? This is my opinion.

Agreed. The title Shifu is thrown about far too freely these days. There was a time when only others would label someone as a master, never themselves.

You are right.

Yes, I have practised Chinese Kung Fu over 40 years and currently I’m ranked the 6th Duan in Chinese martial arts ranking system; but I don’t reckon myself as the one who has mastered what my master passed on to me and that is why I never call myself as “Shifu” or “Master”. To me, being a master meant that you have reached the realm of ‘Martial – Cultural conversion’. Of course, this is just in regards to myself, no reference to others. I really don’t care if my students call me: “Jian” or “Gao”, “Jian Gao” or “Gao Jian”; what I do care is: if this student sincerely appreciates what he or she has been taught about as this is the basic condition of reaching excellence. Because if a student is not sincere to you, how can you teach him or her? I look at the heart of a student, not just the title he or she calling me.

That’s especially important, as a teacher is best judged by the quality of his students.

Exactly! That is why I found that to get a qualified formal student is as difficult as to find a qualified teacher or master.

Up to now, I think I have basically answered this big question for you. So far, this kind of set up is conductive in my club; at the least my current students are aware of what the true Kung Fu is and what the Code of Conduct in Chinese Martial Arts Practice requires for them. As stated in my website: we are unconventional. This method of approach makes us able to leave some unanswered questions for people to work out by themselves in a natural way.

You’ve reached an important area and I appreciate your insight.

Chinese martial arts, if being searched to its extreme end, would be a matter of culture. Chinese Kung Fu actually is not just about fighting arts, it is a school of literature, a heritage, and a spirit. Chinese culture, although has some elements of Legalism (法家) and Mohism (墨家), basically is composite of three philosophies: The Daoist (道家), The Confucianist(儒家)and Buddhist(佛家). Among them, Confucianist (and its religion Confucianism) was the one promoted by most Chinese rulers throughout history. Although derived from the Daoist doctrine, it was developed quite contrary to its origins over thousands of years. It was a major advocate of patriarchy, a promoter of feudal ethical code (封建礼教) and a solvent for the mixture of gentleman and hypocrite.

From my point of view, since the Song Dynasty (宋朝), Chinese society has been dominated by Confucian extremists (not the original Confucianist), the doctrine of feudal ethical code has influenced Chinese social ideology for a long time, even up to now. Acknowledge it or not, as a typical Chinese, we don’t have much sense of what western society (such as Australia) has: the liberty, the equality and the democracy. Chinese martial arts society therefore, as a part of Chinese ‘special’ society, has lots of feudal ethical elements in it. In some cases, it has more strict ethical codes. Almost all the schools in Chinese martial arts have strict etiquette, the hierarchy concept is the very important ‘basic knowledge’ if you become an ‘insider of the martial arts circle (武林中人)’. Normally, there is not much space for liberty, equality and democracy in this area – the masters are the rulers of their schools, the students, especially the disciples would be the ‘pulp’, they do what the master said; if you don’t do it – “get out!” and you are finished.

No doubt, this kind of patriarchal hierarchy is very difficult to be accepted in western world such as Australia. I think this would be a big challenge for promoting traditional Chinese Kung Fu in western countries for both sides (teacher and student).

I agree that for many it is a very foreign concept and in some respects, does not sit well with local values. However, there are also many westerners who crave this aspect of traditional Chinese culture and who are actually attracted to the practice of Kung Fu primarily because of such things.

Maybe you and I look at the matter from a different angle. I acknowledge the attraction of Chinese culture to many westerners, but I’m also aware that ‘to crave’ something doesn’t always give us the right stuff. When China opened its door to the world and to Chinese people in 1980s, lots of Chinese craved the ‘American culture’ at that time; 30 years later, many of these Chinese have found out that such ‘culture’ is not what they needed, at least not 100% needed. Of course, alien culture amazes local people and hence attracts them, but we should distinguish and then pursue the essence of the culture, not the rubbish in it. Daoist, Confucianist and Buddhist are all important philosophies to Chinese culture, but they all have some rubbish in them, especially when people changed the ‘IST’ of philosophies into the ‘ISM’ of religions.

Actually I agree with you that this kind of cultural infatuation is generally not a positive thing. Often people are attracted for the wrong reasons in the first place; unfortunately this can result in a complete and dramatic rejection of all related cultural aspects later when the individual comes to some form of realisation. In some cases this seems to manifest in a borderline racist attitude. For example, there are many Westerners who would prefer to strip Kung Fu of all cultural elements and there seems to be an underlying sense of guilt amongst some for their involvement in a foreign pursuit in the first place.

Here we are! I hope our discussions in this area could be seen by some Chinese martial artists too, especially by some of highly skilled decent Chinese Wushu officials, should this interview been translated into Chinese language. Because, as an extension of our discussion on these two particular questions, what you and I observed and unveiled in here is the true reason why there are so many chaos in Chinese martial arts societies either in China and in the world. Again, this is actually a big subject as culture is a social ideology and it is an expressing way of psychology.

As a traditional Chinese and a traditional Kung Fu practitioner who later on has had the opportunity to compare the ideologies based on cultural differences, particularly after I settled in Australia, I have seen the advantage and disadvantage of these ethical codes in Chinese martial arts society. Surely, we need authority in our martial arts teachings; but it is not necessary to be patriarchal. I’m personally in favour of Daoist, it principally has the elements of liberty, equality and democracy; the most important thing is: it is natural, not artificial. I try to create an environment in which everyone feels they are being treated equally so that their sense of liberty can be released. This way, we can get rid of that rigid relationship in hierarchy; but at the same time, a true sense of Kung Fu skill levels or Kung Fu’s hierarchy can be formed in students mind. To me, this is most important as these students are self inspired naturally. In other words: they are awakening themselves, naturally!

My view on teacher’s title is this: no matter what title you’ve got, it is just a label. Although it is nice to have an attractive label, the important thing is the content. You can be called a master or Shifu or even a grand master and so on, but students are more concerned about the skill level you’ve got.

It’s definitely a consideration. But a good personality is just as, if not more important.

Yes, I agree. Plus, different individuals have different definitions on the name of “master”. Authority in teaching should be formed naturally. As an experienced martial arts practitioner, the lower the profile you keep the more respect you get. Also, your name is your best trade mark, it is for calling anyway! Why shall we put too much artificial titles? This is my opinion.

Agreed. The title Shifu is thrown about far too freely these days. There was a time when only others would label someone as a master, never themselves.

You are right.

Yes, I have practised Chinese Kung Fu over 40 years and currently I’m ranked the 6th Duan in Chinese martial arts ranking system; but I don’t reckon myself as the one who has mastered what my master passed on to me and that is why I never call myself as “Shifu” or “Master”. To me, being a master meant that you have reached the realm of ‘Martial – Cultural conversion’. Of course, this is just in regards to myself, no reference to others. I really don’t care if my students call me: “Jian” or “Gao”, “Jian Gao” or “Gao Jian”; what I do care is: if this student sincerely appreciates what he or she has been taught about as this is the basic condition of reaching excellence. Because if a student is not sincere to you, how can you teach him or her? I look at the heart of a student, not just the title he or she calling me.

That’s especially important, as a teacher is best judged by the quality of his students.

Exactly! That is why I found that to get a qualified formal student is as difficult as to find a qualified teacher or master.

Up to now, I think I have basically answered this big question for you. So far, this kind of set up is conductive in my club; at the least my current students are aware of what the true Kung Fu is and what the Code of Conduct in Chinese Martial Arts Practice requires for them. As stated in my website: we are unconventional. This method of approach makes us able to leave some unanswered questions for people to work out by themselves in a natural way.

Kung Fu brothers Beijing 1980s

Kung Fu brothers Beijing 1980s

One of HARA’s defining principles in particular catches my eye: ‘Practicality is recommended, natural beauty is advocated, serenity is appreciated and relativity is acknowledged’. Excellent sentiments! Is there a phase in the early stages of a students training (particularly in an art as difficult as Liuhe Tanglang) in which natural beauty is perhaps not so encouraged?

The standard is necessary. All arts, including Chinese martial arts, in which any particular style of an art should be kept with its original type as possibly as we can for its purity. Above of this, any art still needs to be developed forward. It depends on individual’s ability in reproduction and innovation. Please don’t forget that we also acknowledge the relativity which means different requirement applies in different situation or phases.

What is the key to developing the relaxed power that is so evident in Liuhe Tanglang?

The nature of water is the key, especially the nature of sea waves.

Do you ever take the time to actually observe waves in action, in order to enhance this understanding? There is certainly plenty of opportunity for it here in Australia.

I experienced the movements of the waves when I was swimming in the sea and I have watched their actions both when I was in China and in Australia. Particularly, when I watched the huge rampage of tsunami and its damage made which was broadcasted in TV.

What is your opinion on combat sports? I know that your teacher was involved in the development of modern sanshou and you yourself have some involvement in its administration in this country.

I personally reckon that K- 1 or UFC are fairer than modern Chinese Sanda (or Sanshou) as Sanda is little bit too much artificially influenced by the competition rules and the referee’s preference. I have seen in many times that when the contestants clinched together, as short as even less than 2 seconds, the fight would be stopped by referee, sometimes it became a protection signals for a particular fighter by the referee. How can we work out who is the actual winner under such situation?

It happened to me in China as well. Any time I had control in the clinch it was instantly broken up.

In real fights, many decisive techniques are carried out during the clinch, fighters need a little longer time (at least over 5 seconds) to implement their tactics during clinches, they need full body contact to make a conversion. The original Chinese martial artists would not like to see what is happing in Sanda or Sanshou today. Similarly, the funny thing happened in Taiji pushing hand competition too. Under the current pushing hand competition rules, the Taiji pushing hand has become a separate contest apart from Chinese Wushu (which is a joke). Actually, the Taiji pushing hand was originally a bridging course or preparation for Taiji practitioners Lei Tai (擂台) fighting.

Very true! Limiting the time in the clinch also reduces the amount of technical options available to the fighter, which could ultimately result in a further ‘dumbing down’ of the sport. Also a very interesting point regarding pushing hands. It has now become a very abstract practice in many ways.

Pushing hand involves some static and dynamic mechanical theories; it requires a very subtle sensitivity and reaction to play. Because of the difficulty for gaining a high level of real skill in it, it always attracts the Taiji ‘Lian Jia(练家)’, but in some cases, those skills have been exaggerated by cheats.

How was sparring trained under Ma Hanqing?

The sparring practice was pretty random during those years from my best memory, because I was not learning Meihua Tanglang with other students at that time, I didn’t do sparring too much with many sparring partners in those days. But I did have the chance to exchange hands with my master, my brother and some of those students who later on became disciples of Ma Hanqing. Beside the distinct figure Ma Lei (the son of Ma Hanqing), some of my Kung Fu brothers have impressed me in those years too. For example: Hu Xilin (胡西林) was one of the outstanding students during those days. Those students who are around my age like Ma Weiling (马卫苓), Ma Shiyong (马士勇), Wang Shenghu (王省虎), Wang Baotai (王宝泰) and Liu Zhigang (刘志刚) were brave fighters in their peak times. I found myself a little vulnerable compared with them when we were young. I also did few casual sparring sessions with little Kung fu brother, Yuan Qiliang (袁启良) in late 1980s who was the runner up in Chinese national Sanda championship at that time. Of course, I was not at his Sanda level too. The senior Kung Fu brother Wang Xishun (王希顺) with whom I attended our disciple’s ceremony in 1983 was an instructor of professional Wushu Team in Shanxi province (山西) at that time, I never got chance to exchange hands with him, I was too young for him anyway --- Among Kung Fu brothers, Ma Weiling is one of those who’s both knowledge and techniques are very rich and he has personally helped me a lot.

The standard is necessary. All arts, including Chinese martial arts, in which any particular style of an art should be kept with its original type as possibly as we can for its purity. Above of this, any art still needs to be developed forward. It depends on individual’s ability in reproduction and innovation. Please don’t forget that we also acknowledge the relativity which means different requirement applies in different situation or phases.

What is the key to developing the relaxed power that is so evident in Liuhe Tanglang?

The nature of water is the key, especially the nature of sea waves.

Do you ever take the time to actually observe waves in action, in order to enhance this understanding? There is certainly plenty of opportunity for it here in Australia.

I experienced the movements of the waves when I was swimming in the sea and I have watched their actions both when I was in China and in Australia. Particularly, when I watched the huge rampage of tsunami and its damage made which was broadcasted in TV.

What is your opinion on combat sports? I know that your teacher was involved in the development of modern sanshou and you yourself have some involvement in its administration in this country.

I personally reckon that K- 1 or UFC are fairer than modern Chinese Sanda (or Sanshou) as Sanda is little bit too much artificially influenced by the competition rules and the referee’s preference. I have seen in many times that when the contestants clinched together, as short as even less than 2 seconds, the fight would be stopped by referee, sometimes it became a protection signals for a particular fighter by the referee. How can we work out who is the actual winner under such situation?

It happened to me in China as well. Any time I had control in the clinch it was instantly broken up.

In real fights, many decisive techniques are carried out during the clinch, fighters need a little longer time (at least over 5 seconds) to implement their tactics during clinches, they need full body contact to make a conversion. The original Chinese martial artists would not like to see what is happing in Sanda or Sanshou today. Similarly, the funny thing happened in Taiji pushing hand competition too. Under the current pushing hand competition rules, the Taiji pushing hand has become a separate contest apart from Chinese Wushu (which is a joke). Actually, the Taiji pushing hand was originally a bridging course or preparation for Taiji practitioners Lei Tai (擂台) fighting.

Very true! Limiting the time in the clinch also reduces the amount of technical options available to the fighter, which could ultimately result in a further ‘dumbing down’ of the sport. Also a very interesting point regarding pushing hands. It has now become a very abstract practice in many ways.

Pushing hand involves some static and dynamic mechanical theories; it requires a very subtle sensitivity and reaction to play. Because of the difficulty for gaining a high level of real skill in it, it always attracts the Taiji ‘Lian Jia(练家)’, but in some cases, those skills have been exaggerated by cheats.

How was sparring trained under Ma Hanqing?

The sparring practice was pretty random during those years from my best memory, because I was not learning Meihua Tanglang with other students at that time, I didn’t do sparring too much with many sparring partners in those days. But I did have the chance to exchange hands with my master, my brother and some of those students who later on became disciples of Ma Hanqing. Beside the distinct figure Ma Lei (the son of Ma Hanqing), some of my Kung Fu brothers have impressed me in those years too. For example: Hu Xilin (胡西林) was one of the outstanding students during those days. Those students who are around my age like Ma Weiling (马卫苓), Ma Shiyong (马士勇), Wang Shenghu (王省虎), Wang Baotai (王宝泰) and Liu Zhigang (刘志刚) were brave fighters in their peak times. I found myself a little vulnerable compared with them when we were young. I also did few casual sparring sessions with little Kung fu brother, Yuan Qiliang (袁启良) in late 1980s who was the runner up in Chinese national Sanda championship at that time. Of course, I was not at his Sanda level too. The senior Kung Fu brother Wang Xishun (王希顺) with whom I attended our disciple’s ceremony in 1983 was an instructor of professional Wushu Team in Shanxi province (山西) at that time, I never got chance to exchange hands with him, I was too young for him anyway --- Among Kung Fu brothers, Ma Weiling is one of those who’s both knowledge and techniques are very rich and he has personally helped me a lot.

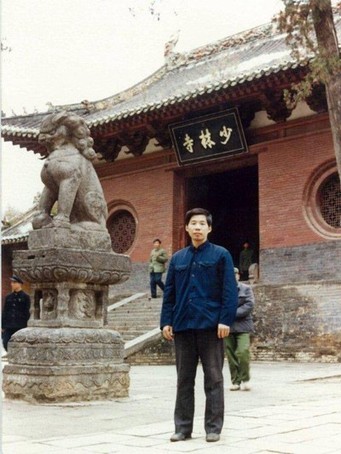

Shaolin Si, 1986

Shaolin Si, 1986

I know that you are a peaceful guy and a follower of the way, but I subject all of my interviewees to the same question – do you have any personal fight stories to share? If so, we’d love to hear because that stuff is inspirational.

I will probably surprise you a bit on this question: Although my temperament has been modified to certain degrees now (thanks to a long time Taiji practice), it is basically a little bit explosive which certainly put me in trouble sometimes. Sorry I cannot tell any personal fights under self defence situation as those are private matters.

Fair enough.

For ‘friendly’ or ‘try out’ matches, I have met quite a few people ranging from ‘intruders’ to some very experienced martial artists or high ranking masters, all of which were involved with Taiji art, only except one sort of ‘serious’ challenge in the year 1987 which was not a personal scuffle; rather, it was merely based on verifying different believes in regarding to different styles. It is still like what happened yesterday and in the end, both involved sides were happy; so I can share this one only as a response to this particular question.

It was a winter morning in the year 1987. As usual, I came to a small local park not far from my home. There were not many people in the park under such sub- zero temperatures in the early morning. Before I started to practise my Wu Style Taiji routine (I normally practised Taiji in the morning and practised Liuhe Tanglang in the evening during those days), one man’s movements caught my eyes: he was aged in his middle 50’s, average size but solid build, his movements were very slow, sometimes they looked as if nearly stopped; but somehow I could feel that there was something in his body started linking up the next movement: it was the energy in his body wriggling like a moving worm. Through the morning rays, a little white steam could be seen over his bald head - amazing! From my intuition, I knew that this was a high level ‘Lian Jia (练家)’ which means: a high level Kung Fu practitioner. For a quite long while, I forgot to do anything but to watch the man’s practice until he finished his routine. “Hello! Yours Kung Fu are amazing!” I greeted, he looked at me first then smiled: “Do you practise Taiji?” he asked, “Yes, I do Wu Style (吴氏).” I answered, “What is yours? Shifu ---” “My Surname is X (Sorry, I can’t tell his real name), mine is Wu/Hao Style (武氏).” Well! This was the first time I saw a man practising such style like this! “Do you practise pushing hand?” he asked, “yes, but I’m not very good in it.” I replied. “Would you like to give it a go with me?” he said, “of course, I’d love to learn something!” I was more than pleased. Then followed a pleasant pushing hand practice; during the practise, he confirmed my Taiji level and corrected some of my problems. It was a very happy day.

The next morning was a similar situation but he started teaching me like he was my teacher. It was a strange feeling: on one had you are appreciative, on the other hand, you feel a little bit embarrassed. Well, he was more experienced than me and much older than me. I kept my student manner without challenging. In the third morning, we had a little argument when he told me that only Taiji was the best Chinese martial art form his experience. He said that lots of his former opponents had converted from other styles of Kung Fu or other schools of Taiji to his school. I disagreed with his opinion and told him: although my master and I were all started our martial arts journey from Taiji learning, we did not reckon Taiji was the best Chinese martial art from the view of our other style’s practise; it should be dependant on relativity --- My opinion obviously upset him a bit, he asked what my other style was, I told him: it was Praying Mantis Boxing, but I did not mention the name of Liuhe Tanglang. He then challenged me if I’d like to try out mine with his; I confirmed I would.

Excellent! I’m glad I asked this question...

We selected the time and venue (same day’s evening at the same park under the lights). For the safety reason, I suggested that we’d better wear the fingerless gloves to protect both sides; he agreed. Because he didn’t have such gloves, I agreed to supply two pairs for the ‘try out’. It was the evening; we both came to the venue on time. No more talk, I passed a pair of gloves to him and put on mine. When he said he was ready, we approached towards each other. At that moment, my feeling was just like I was going hunting – I saw his eyes glare and his subtle movements but there was no hesitation for me. We both shifted, looking for the right opportunity. At the moment when I located his head, I knew that I’ve got the right opportunity. Of course I also saw his right hand’s approaching, but I knew how to handle it – with my ‘Crossed Conical Fist (十字锥棰)’! I started my attack, although I reserved about 1/3 of my energy, the rest of mine was still a unified punching power, it was on and I was sure that I got my target. Almost simultaneously (maybe just a little later), I felt that he got me too as his explosive power passed by my left arm running through my both feet and I was floated, being sent off about 2 meters away from him – a typical Taiji Fajin(发劲)!

Nice one. There’s nothing like experiencing someone’s power (as opposed to just hearing about it).

I will probably surprise you a bit on this question: Although my temperament has been modified to certain degrees now (thanks to a long time Taiji practice), it is basically a little bit explosive which certainly put me in trouble sometimes. Sorry I cannot tell any personal fights under self defence situation as those are private matters.

Fair enough.

For ‘friendly’ or ‘try out’ matches, I have met quite a few people ranging from ‘intruders’ to some very experienced martial artists or high ranking masters, all of which were involved with Taiji art, only except one sort of ‘serious’ challenge in the year 1987 which was not a personal scuffle; rather, it was merely based on verifying different believes in regarding to different styles. It is still like what happened yesterday and in the end, both involved sides were happy; so I can share this one only as a response to this particular question.

It was a winter morning in the year 1987. As usual, I came to a small local park not far from my home. There were not many people in the park under such sub- zero temperatures in the early morning. Before I started to practise my Wu Style Taiji routine (I normally practised Taiji in the morning and practised Liuhe Tanglang in the evening during those days), one man’s movements caught my eyes: he was aged in his middle 50’s, average size but solid build, his movements were very slow, sometimes they looked as if nearly stopped; but somehow I could feel that there was something in his body started linking up the next movement: it was the energy in his body wriggling like a moving worm. Through the morning rays, a little white steam could be seen over his bald head - amazing! From my intuition, I knew that this was a high level ‘Lian Jia (练家)’ which means: a high level Kung Fu practitioner. For a quite long while, I forgot to do anything but to watch the man’s practice until he finished his routine. “Hello! Yours Kung Fu are amazing!” I greeted, he looked at me first then smiled: “Do you practise Taiji?” he asked, “Yes, I do Wu Style (吴氏).” I answered, “What is yours? Shifu ---” “My Surname is X (Sorry, I can’t tell his real name), mine is Wu/Hao Style (武氏).” Well! This was the first time I saw a man practising such style like this! “Do you practise pushing hand?” he asked, “yes, but I’m not very good in it.” I replied. “Would you like to give it a go with me?” he said, “of course, I’d love to learn something!” I was more than pleased. Then followed a pleasant pushing hand practice; during the practise, he confirmed my Taiji level and corrected some of my problems. It was a very happy day.

The next morning was a similar situation but he started teaching me like he was my teacher. It was a strange feeling: on one had you are appreciative, on the other hand, you feel a little bit embarrassed. Well, he was more experienced than me and much older than me. I kept my student manner without challenging. In the third morning, we had a little argument when he told me that only Taiji was the best Chinese martial art form his experience. He said that lots of his former opponents had converted from other styles of Kung Fu or other schools of Taiji to his school. I disagreed with his opinion and told him: although my master and I were all started our martial arts journey from Taiji learning, we did not reckon Taiji was the best Chinese martial art from the view of our other style’s practise; it should be dependant on relativity --- My opinion obviously upset him a bit, he asked what my other style was, I told him: it was Praying Mantis Boxing, but I did not mention the name of Liuhe Tanglang. He then challenged me if I’d like to try out mine with his; I confirmed I would.

Excellent! I’m glad I asked this question...

We selected the time and venue (same day’s evening at the same park under the lights). For the safety reason, I suggested that we’d better wear the fingerless gloves to protect both sides; he agreed. Because he didn’t have such gloves, I agreed to supply two pairs for the ‘try out’. It was the evening; we both came to the venue on time. No more talk, I passed a pair of gloves to him and put on mine. When he said he was ready, we approached towards each other. At that moment, my feeling was just like I was going hunting – I saw his eyes glare and his subtle movements but there was no hesitation for me. We both shifted, looking for the right opportunity. At the moment when I located his head, I knew that I’ve got the right opportunity. Of course I also saw his right hand’s approaching, but I knew how to handle it – with my ‘Crossed Conical Fist (十字锥棰)’! I started my attack, although I reserved about 1/3 of my energy, the rest of mine was still a unified punching power, it was on and I was sure that I got my target. Almost simultaneously (maybe just a little later), I felt that he got me too as his explosive power passed by my left arm running through my both feet and I was floated, being sent off about 2 meters away from him – a typical Taiji Fajin(发劲)!

Nice one. There’s nothing like experiencing someone’s power (as opposed to just hearing about it).

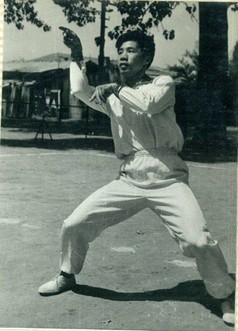

Tanglang Feng Shou

Tanglang Feng Shou

But I was able to neutralise a bit to maintain my balance (thanks to the Taiji pushing hand training!). I checked myself: I was standing and there was not hurt; I was all right. I quickly adjusted my stance and prepared to give another round of fight. I glanced at my opponent: he was standing too, but somehow his mouth was deformed a little bit and there was something running out of his mouth – no good, he was bleeding! No need to continue anymore! “Shall we stop the fight please?” I suggested; “What?” he asked; “You are bleeding.” I pointed out. He then realised his problems and looked embarrassed --- It might be just about one minute and the fight was over. “Can you please not hit my head?” he asked; “What I was looking for was you head first and this is our tactic.” I replied. “Your punch was a bit like Western boxing, wasn’t it?” he looked like recalling; “No, it is not Western boxing, but it is a kind of Praying Mantis Boxing.” I replied.” What kind of Praying Mantis Boxing was it?” he looked confused; “Liuhe Tanglang.” “Oh, I wonder why I didn’t see this one before --- Yeah; I think my school needs something to improve.” He looked a little frustrated.

He certainly took it very well though...

The next morning, we met in the park again, he told me that he was pleased to know my Tanglang techniques; as an appreciation for the fight, he give me his noted chart on Dian Xue/Dim Mak (点穴脉) and the explanation for it; I sincerely thanked him then quickly ran back to my home picking up a basket of eggs as my appreciation for his sincerity (eggs were still pretty dear presents at that time). He accepted my present then told me that he had learned a lesson from the fight although he had practised 30+ years of Taiji Kung Fu and that he was leaving for his home town in Northeast (东北). We said “All the best” to each other and then he left. It was a shame I never got the chance to see him again (I came to Australia in 1988). To be honest, although he lost the challenge (I guess I was probably a little lucky), his amazing Taiji skill and his decent personally as a Taiji master or a high level Kung Fu Lian Jia (功夫练家) have deeply impressed me indeed; his spirit in pursuing his beloved martial arts has also set a dignified example for myself – A true man (好汉)!

Yes, what a great example he was. I could only hope to be as gracious in defeat.

He certainly took it very well though...

The next morning, we met in the park again, he told me that he was pleased to know my Tanglang techniques; as an appreciation for the fight, he give me his noted chart on Dian Xue/Dim Mak (点穴脉) and the explanation for it; I sincerely thanked him then quickly ran back to my home picking up a basket of eggs as my appreciation for his sincerity (eggs were still pretty dear presents at that time). He accepted my present then told me that he had learned a lesson from the fight although he had practised 30+ years of Taiji Kung Fu and that he was leaving for his home town in Northeast (东北). We said “All the best” to each other and then he left. It was a shame I never got the chance to see him again (I came to Australia in 1988). To be honest, although he lost the challenge (I guess I was probably a little lucky), his amazing Taiji skill and his decent personally as a Taiji master or a high level Kung Fu Lian Jia (功夫练家) have deeply impressed me indeed; his spirit in pursuing his beloved martial arts has also set a dignified example for myself – A true man (好汉)!

Yes, what a great example he was. I could only hope to be as gracious in defeat.

With Ma Lei and Yuan Qiliang, Beijing 2007

With Ma Lei and Yuan Qiliang, Beijing 2007

What is your opinion on the theory of the relationship between Xinyiliuhe and Liuhe Tanglang Quan? Beyond theoretical commonalities, do you see any true relationship between it and any other Liuhe style?

As I said before, the nature of Liuhe Tanglang can be expressed by the table tennis terminology -‘快攻加弧圈’. This nature is also the nature of Xingyi Quan which was derived from Xin Yi Liuhe. The most common character between the two is their bursting momentum which is quite dangerous. From my practising experience, I have also found a close relationship between Liuhe Tanglang and Taiji as both of them have the characteristics of ’Zhan, Nian, Lian, Sui’ - (粘,黏,连,随); which can be expressed as ‘弧圈’ in Chinese table tennis terminology. So far, I haven’t found any true relationship between Liuhe Tanglang and other Liuhe style martial arts.

Although Liuhe Tanglang has ‘soft’ characteristics which set it apart from other forms of Tanglang, it is evident that it has in fact much in common with its Meihua and Qixing family brothers. We share not only common techniques such as: gou shou; feng shou (and shuang feng shou); mopan shou; dengta; dengpu; and, furen jiao, but it appears that our classical quan pu is also based around Luohan Xinggong Duanda.

Do you mean: 《罗汉行功短打》?

Yes.

In regards to the true author of this manuscript, it still remains to be verified. But no doubt all kinds of Tanglang Quan belong to ‘Duan Da’ category. Of course, Liuhe Tanglang has lots of common techniques shared with its siblings in the Tanglang Quan family.

Did Ma Hanqing ever use name variants for Liuhe Tanglang?

He normally called it as ‘Liuhe’ or ‘Liuhe Tanglang Quan’ although he told me about the name of ‘Ma Hou Tanglang’ (马猴螳螂) because of the external manner of the style.

As I said before, the nature of Liuhe Tanglang can be expressed by the table tennis terminology -‘快攻加弧圈’. This nature is also the nature of Xingyi Quan which was derived from Xin Yi Liuhe. The most common character between the two is their bursting momentum which is quite dangerous. From my practising experience, I have also found a close relationship between Liuhe Tanglang and Taiji as both of them have the characteristics of ’Zhan, Nian, Lian, Sui’ - (粘,黏,连,随); which can be expressed as ‘弧圈’ in Chinese table tennis terminology. So far, I haven’t found any true relationship between Liuhe Tanglang and other Liuhe style martial arts.

Although Liuhe Tanglang has ‘soft’ characteristics which set it apart from other forms of Tanglang, it is evident that it has in fact much in common with its Meihua and Qixing family brothers. We share not only common techniques such as: gou shou; feng shou (and shuang feng shou); mopan shou; dengta; dengpu; and, furen jiao, but it appears that our classical quan pu is also based around Luohan Xinggong Duanda.

Do you mean: 《罗汉行功短打》?

Yes.

In regards to the true author of this manuscript, it still remains to be verified. But no doubt all kinds of Tanglang Quan belong to ‘Duan Da’ category. Of course, Liuhe Tanglang has lots of common techniques shared with its siblings in the Tanglang Quan family.

Did Ma Hanqing ever use name variants for Liuhe Tanglang?

He normally called it as ‘Liuhe’ or ‘Liuhe Tanglang Quan’ although he told me about the name of ‘Ma Hou Tanglang’ (马猴螳螂) because of the external manner of the style.

With Ma Weiling and Ma Shiyong, Beijing 2010

With Ma Weiling and Ma Shiyong, Beijing 2010

Ma Hanqing ended up in Heilongjiang towards the end of the Cultural Revolution – establishing a wuguan at Daqing. Have you ever had the chance to connect with any of his Dongbei (north-eastern) descendants?

Not yet.

Have you had the opportunity to meet and exchange with the descendants of Shan Xiangling in Shandong, Dongbei or Inner Mongolia? In recent years some Beijing-based practitioners seem to have travelled to Longkou to supplement their training.

Not yet up to now. But I’d love to go to Long Kou (龙口) or Zhao Yuan (招远) one day, either with my Kung Fu brothers, my students or by myself.

The Dongbei region is a hotbed of martial arts. I have heard it said that Ma Hanqing had to forcefully establish himself in Daqing and his opponents were certainly no walk-overs. Did he share any tales of his encounters there?